— Clinical

Trials By Dire

UC San Diego Health was part of three of the first four clinical trials resulting in approved COVID-19 vaccines, and has conducted more than two dozen other investigations of potential drugs and therapies

On December 11, 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) gave emergency use authorization (EUA) to the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. Seven days later, it granted EUA to the Moderna vaccine. On February 27, 2021, an EUA was given to the Janssen/Johnson & Johnson vaccine. At this writing, clinical trials data for a fourth major vaccine — AstraZeneca — had not yet been submitted for FDA review.

One year earlier, none of these vaccines existed; all were the product of intense, accelerated development that included international clinical trials involving hundreds of thousands of participants and expedited review. In three of the four trials — Moderna, Janssen/Johnson & Johnson and Astra-Zeneca — UC San Diego Health and local residents played roles.

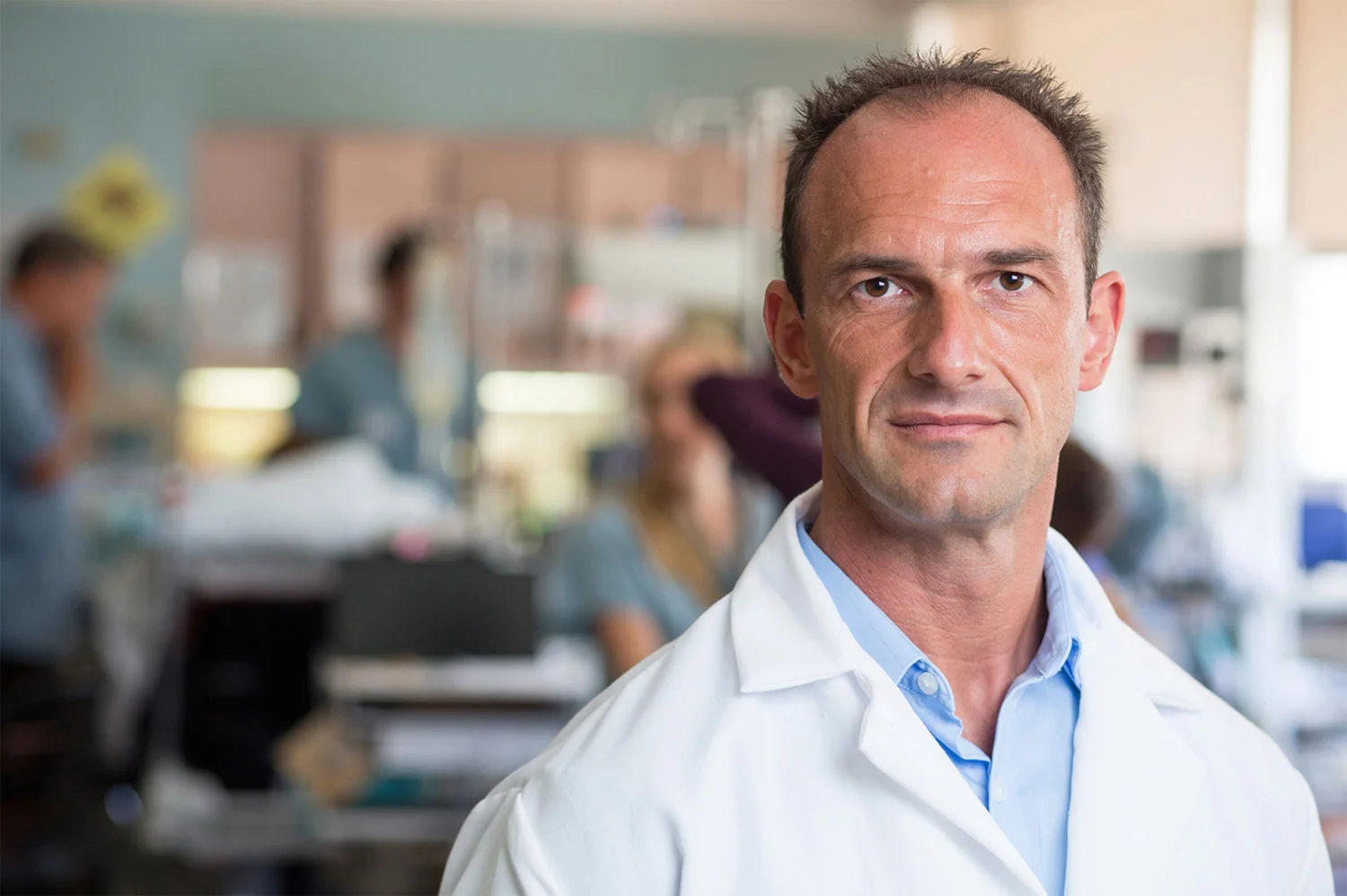

“It’s not really surprising,” said Gary Firestein, MD, Distinguished Professor of Medicine and director of the Altman Clinical and Translational Research Institute (ACTRI). “UC San Diego is an international research hub where thousands of clinical trials are conceived or conducted every year, for almost every human condition imaginable.

— Gary Firestein, MD“The ability to combine a deep bench of experienced investigators with all of the necessary tools and resources makes UC San Diego a natural, go-to destination for clinical trials, and that means San Diegans often get first access to the latest advances in medical science.”

Gary Firestein, MD (left) is Distinguished Professor of Medicine and director of the Altman Clinical and Translational Research Institute, with project scientist Deepa Hammaker, PhD.

“The ability to combine a deep bench of experienced investigators with all of the necessary tools and resources makes UC San Diego a natural, go-to destination for clinical trials, and that means San Diegans often get first access to the latest advances in medical science.”

And notably, Firestein added, ACTRI investigators were “extremely successful” in recruiting trial participants from underserved and underrepresented communities, a critical element in developing therapeutics that are reflective and effective across all demographics. In the Moderna study, for example, approximately 80 percent of participants in the second (and last) month of recruitment were Hispanic/Latinx.

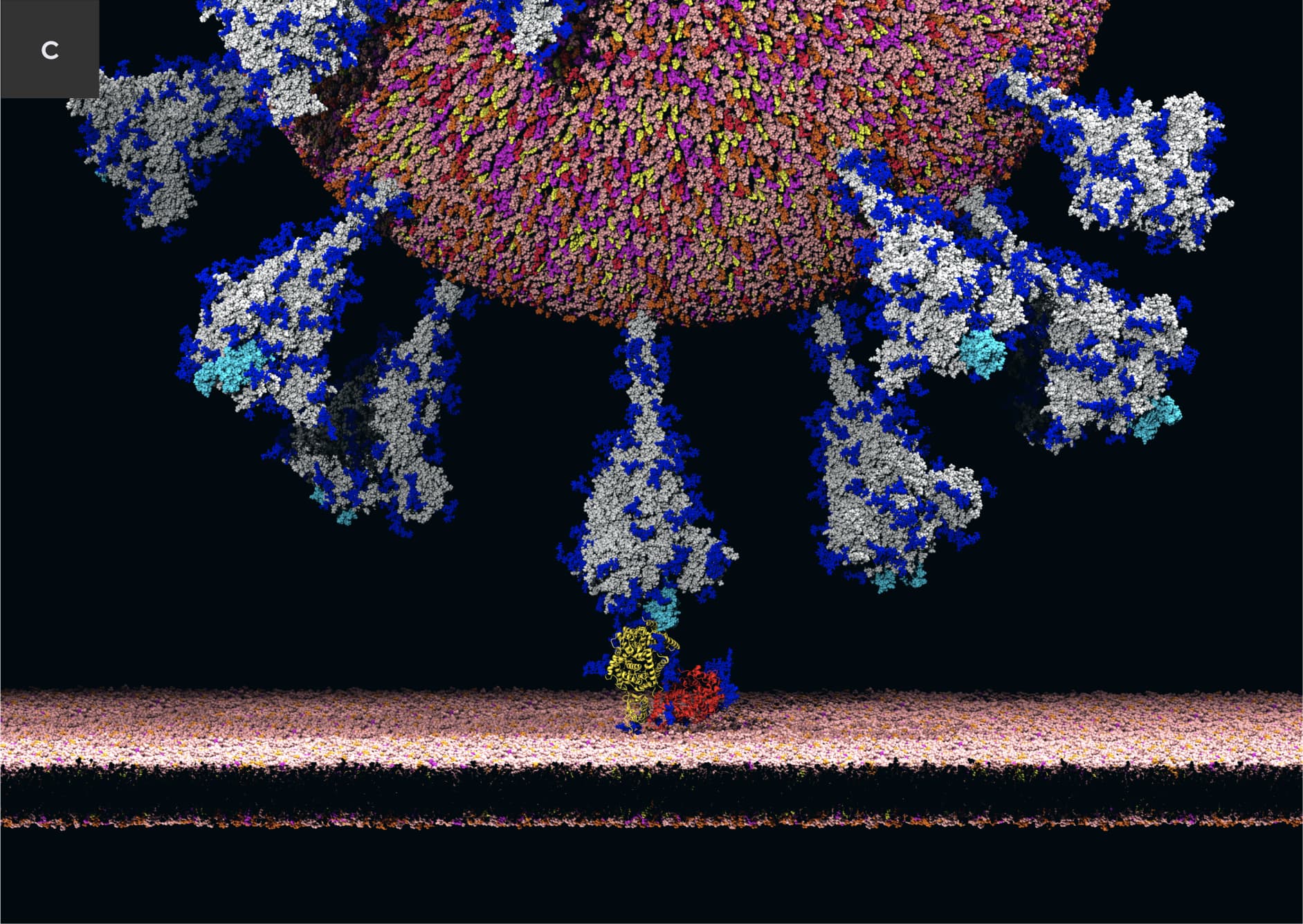

The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are based on messenger RNA (mRNA) technology. These vaccines provide cells with instructions to produce a harmless piece of the virus’ characteristic spike protein. The human immune system recognizes the spike protein as “foreign” and builds an immune response against it. Later, if vaccinated persons are exposed to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, their immune systems are already prepared to help prevent infection and illness.

The Astra-Zeneca and Janssen vaccines employ an older approach: An inactivated common cold virus is modified to carry SARS-CoV-2’s spike protein, which the virus uses to enter host cells, spurring the immune system to create neutralizing antibodies that essentially render subsequent exposures to the coronavirus as non-infectious.

Astra-Zeneca and Janssen are built on much-documented vaccine platforms that had worked well with other diseases, including HIV, Ebola and malaria, said Susan Little, MD, professor of medicine at UC San Diego School of Medicine and principal investigator for both UC San Diego trials.

MRNA vaccines are easier and faster to develop, but until the pandemic, the approach had never been approved for human use. “The world was facing an unprecedented crisis; millions infected, hundreds of thousands of people already dead,” said Stephen Spector, MD, Distinguished Professor of Pediatrics and principal investigator in San Diego for the Moderna trial. “A vaccine was desperately needed, as soon as possible.”

— Stephen Spector, MD.“The world was facing an unprecedented crisis, millions infected, hundreds of thousands of people already dead.”

All of the trials, both in San Diego and around the world, were accelerated efforts, conducted over the course of months, not the usual five to 10 years. That alacrity demanded spending billions of dollars and making some educated guesses.

For example, drug manufacturers said injections of the two-dose Pfizer and Moderna vaccines should be given 21 and 28 days apart, respectively, but those intervals were set, in part, to hasten data collection and speed review. Eventually, the Centers for Disease Control said dose intervals could be up to 42 days apart with no negative consequences, and longer intervals may actually produce a more robust immune response.

Initial clinical trial data indicated all of the EUA-granted vaccines were strongly effective against SARS-CoV-2. Concerns grew, however, that the vaccines were less effective against new virus variants emerging around the world, from the United Kingdom and South Africa to Brazil and India. Subsequent data suggests the vaccines remain effective, both preventing infection and dramatically reducing the risk of severe disease and hospitalization.

Davey Smith, MD, is a translational research virologist and head of Infectious Diseases and Global Public Health at UC San Diego School of Medicine. He works in both vaccine development and in studying viral variants.

“It’s the nature of SARS-CoV-2, like all viruses, to evolve, to adapt to any challenges that might threaten survival. COVID-19 vaccines will need to be modified and improved going forward. Every year, the flu shot is a different formulation. Something similar might be necessary with SARS-CoV-2 and future variants to keep the virus under control.”

Much effort now focuses on refining current vaccines, creating new options and developing boosters. One question still to be fully resolved is how long do current vaccines remain effective. One clinical trial involving UC San Diego will try to provide answers, comparing transmission and infection rates between two groups of students, one vaccinated, the other not.

Other clinical

trials

Vaccines were not the only target of COVID-19 trials at UC San Diego Health. More than two dozen have been launched, many assessing new or repurposed drugs and therapies.

For example, UC San Diego Health researchers have been involved in clinical trials assessing the antiviral drug remdesivir and the repurposed drugs tocilizumab, used to treat arthritis and other inflammatory diseases, and ramipril, used to treat hypertension.

They are studying the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in cancer patients and the likely outcomes of chronic kidney disease patients with COVID-19 infections. And they are evaluating viral transmission risk of persons fully inoculated with the Moderna vaccine and among asymptomatic children.